Chicago’s South Side Was Big Part of the Civil Rights Era

Chicago’s South Side Was Big Part of the Civil Rights Era

BY WENDELL HUTSON

Contributing Writer

The civil rights era may have begun in the south, but made its way through Chicago’s South Side by way of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who delivered one of his first Chicago speeches at the University of Chicago (U of C).

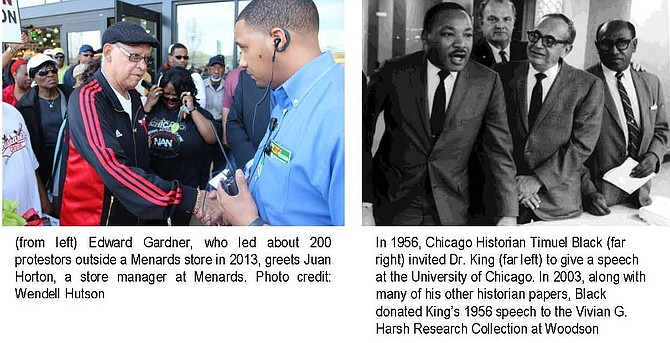

On April 13, 1956, a 27-year-old King spoke at the Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, 5850 S. Woodlawn Ave., after being invited by Chicago historian Timuel Black, who earned a master’s degree in social science two years earlier at the University of Chicago.

In 2003, Black donated many of his historian papers, including the 1956 speech King gave at the U of C, to the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection at Woodson Regional Library, 9525 S. Halsted St.

“We cannot slow up, because we have a date with destiny and we must move with all deliberate speed,” King told a standing room only crowd at the chapel in 1956.

In total, King visited the U of C three times between 1956 and 1966 during an era when he received the Noble Peace Prize in 1964, and then Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The more King came to Chicago, said Black, the larger his followers became as he preached justice, peace and equality for all.

“We are, in the South, moving from a negative peace, where Negroes accept a subordinate place in society, to a positive peace, where all people live in equality,” King said on Oct. 25, 1959 during a Sunday worship service at the chapel.

King’s last U of C visit was on Jan. 27, 1966, one day after he moved his family into a West Side apartment building. The 39-year-old Baptist preacher was shot dead by a lone gunman while in Memphis, Tenn. with other civil rights leaders including the Rev. Jesse Jackson on April 4, 1968.

That day changed Black America forever said Black, a 100-year-old Washington Park resident.

“Things were never the same in America for blacks after King was killed,” contends Black. “This man stood up for ‘us’ and he died for us too and that is something black folks will never forget.”

Black helped organize marches and protest demonstrations for King when he visited Chicago, and said he did so because he believed in his message of hope. And on Aug. 28, 1963, Black, a Chicago teacher at the time, was among the 250,000 people that stood in the mall in Washington, D.C. to hear King’s famous “I Have A Dream” speech.

“I was impressed that a young, black man cared enough about us black folks to speak out against injustices even if it meant becoming a ‘target’ by whites,” recalled Black. “His courage and determination to see justice at any cost was remarkable and really inspired me to want to become apart of his movement for change in America.”

But even with all the accomplishments King made in Chicago and around the world, Black pointed out some lingering issues that remain a challenge today like housing.

“Housing segregation still exists in Chicago. More unity is needed in the black community,” said Black. “Nowadays there’s a unique class-separation, but back when I was growing up, there was no class-separation among blacks. We all looked alike and we all lived in the same neighborhoods.”

He added that during his generation, black kids lived at home with both parents, but now black kids are growing up in households with no male role models.

“There were mostly two-parent households back then, but today that is less than 35 percent,” contends Black. “The community has disconnected itself from helping families and now we have a bunch of single mothers raising children with no help from the community.”

A contributing reason why so many black youth are involved in crimes like murder and selling illegal drugs is because young people do not plan for the future, explained Black.

“The reason you see so many young people shooting each other is because they do not believe there is a future for them and they just don’t care about their actions,” added Black. “That’s why you don’t see more young people voting and getting involved with their community.”

Fast forwarding to more than 40 years after King was murdered, the fight for equality in Chicago continues. Only these days, it’s by more modern civil rights leaders like entrepreneur Edward Garner, who founded the former Soft Sheen Products Co. in 1964 with his wife in the basement of his South Side home.

These days, Gardner, 95, spends much of his time with family but remains passionate about blacks getting what he described as “their fair share of the pie.” In 2012, he went on a citywide crusade shutting down construction sites (especially those in black neighborhoods) whose workers did not include any blacks.

One year later in 2013, Gardner led about 200 protesters who marched outside Menards, 9100 S. Western Ave., in Evergreen Park because he said there were no black construction workers used to build the store.

While today’s civil rights leaders in Chicago have done remarkable work, Dr. King would be both proud and disappointed that more has not been done since his death, said former U.S. Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr., who was the keynote speaker at a Jan. 20 Dr. King event in Harvey.

“I never met Dr. King obviously because I was just a little boy during his era but I have studied his work and have always tried to do my part as a civil rights believer and supporter,” Jackson Jr. told the Citizen. “Dr. King would be proud of the efforts we as a nation have made when it comes to equality for all. But I think he would also be disappointed with the limited accomplishments this country has made since giving up his life for us.”

So much has changed in Chicago for blacks thanks to King’s efforts, contends Jackson Jr.

Housing segregation has been outlawed so blacks can live anywhere they desire, although there still remains an unwritten boundary when it comes to ‘well-to-do’ areas.

Hyde Park has a population of 24,100 and 52 percent are white while 28 percent are black and historically, it has been a majority white neighborhood, according to census data. But more black families now reside in the South Side neighborhood, such as President Barack Obama and the Nation of Islam’s Minister Louis Farrakhan.

And blacks can now attend public schools with whites even though it was once illegal to do so. Wendell Phillips High School is in Bronzeville and was built in 1904 as the first public high school in Chicago whose students were predominately black even though Phillips himself was a white abolitionist and attorney.

“See what I mean when I say while we have come a long way and achieved many things we still have much work that needs to be done before we can truly be proud of ourselves as a nation,” said Jackson Jr.

Latest Stories

- Happy New You!

- Is It Normal Aging or Early Dementia? Memory Loss Causes and Alzheimer’s Warning Signs to Watch For

- Chicago Sinfonietta To Host ‘Open Heart’ Concert

- State Of The Southland: Village of Matteson

- Local Woman Looks To Change Narrative Around Having Locs

Latest Podcast

Wendy Thompson-Friend Health